Cairngorms Cranes

#WildlifeComeback

A wetland icon is missing from Scotland’s largest and wildest National Park. The Cairngorms Cranes project is on a mission to change that.

We need an ambassador for scaling up the restoration of our denuded wetlands. Step forward the crane.

Lake Hornborga in western Sweden is the stage for a wildlife spectacle that once experienced, lives long in the memory. Each spring, around 20,000 Eurasian cranes gather, before the final leg of a long migration to their northern breeding grounds. The cacophonous convention is a magnet for birdwatchers and wildlife enthusiasts, attracted from around Europe and beyond to watch cranes dance and bugle in ritualistic courtship displays. For many Swedes, this ‘Crane Festival’ is an annual pilgrimage, and for the birds, it’s where lifelong bonds are re-established, and new ones forged. In modern Scotland, there are few wildlife displays that compete on this scale.

The 20,000 cranes that visit Lake Horborga each spring, are almost matched in number by those wishing to experience their spectacular courtship rituals.

Cranes were once widespread across Britain, leaving many place names featuring ‘Cran’ as a marker of their importance. Within Scotland, their bones have been found in Edinburgh, the Borders, Moray, the Western Isles and Orkney, while references to cranes in the Gaelic and Old Welsh origins of place names and historic battles within the Cairngorms, give strong indications of their former presence here. Today though, in their absence, our wetlands are muted.

The UK has lost 90% of its wetlands over the last 100 years.

Prized for their meat, eggs and feathers, and displaced through the drainage of wetlands for human settlement and farming, cranes are thought to have become extinct as a breeding species on the mainland in the late 1500s. Their tasty flesh made them a star attraction at medieval banquets: 115 were served at the Christmas feast of Henry III at York in 1251, and a further 204 marked the celebration of George Neville’s enthronement as Archbishop of York in 1465. They would soon become a rarity, however, with even those surviving longer on our islands – a flock of 60 cranes was recorded on the Isle of Skye during the late 17th century – eventually succumbing to the pressure of over-hunting and habitat loss.

The disappearance of cranes from our shores did little to slow the loss of their former breeding grounds. The UK has lost 90% of its wetlands over the last 100 years. Imagine that – for every 10 dynamic marshes and mires, flood plains and pools that existed in the early 1900s, only one now remains. Worldwide, wetlands are disappearing three times faster than natural forests, which sees us losing not just a rich array of life, but a vital tool in combatting drought and flooding. Peatlands are also a key element of wetland ecosystems, and when these are drained, dried and removed for fuel or horticulture, we lose a carbon store that holds twice as much carbon dioxide as rainforest.

With climate change knocking on Scotland’s door, work to reinstate and reconnect our wetlands is underway across large upland areas. Increasingly, their role in locking up carbon and reducing the impacts of severe seasonal flooding is being recognised, and the critical restoration work funded. But habitat restoration is a notoriously difficult story to tell, and wetlands would benefit from a mascot – an emblematic ambassador for scaling up the rewilding of our denuded landscapes. Step forward the crane. Standing at more than a metre tall, with a wingspan of up to 2.5 metres, this charismatic and highly visible species has the personality and presence to ramp up ambition for more and bigger wetlands.

This is about reshaping how we perceive and value nature.

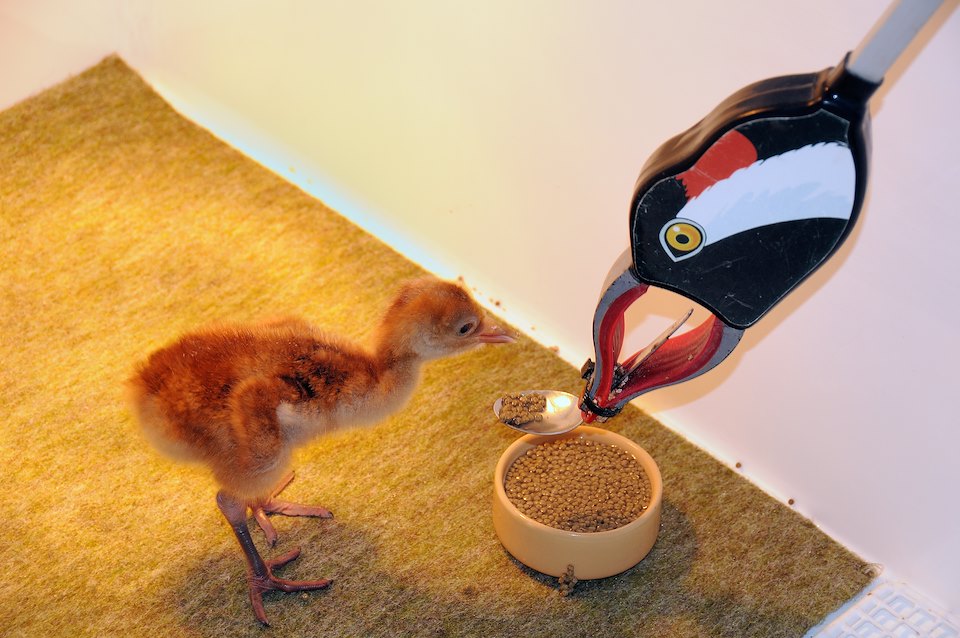

Led by SCOTLAND: The Big Picture, the Cairngorms Cranes project seeks to put the crane back on Scotland’s wildlife map. Working in partnership with Trees for Life and the Cairngorms National Park Authority, SBP will engage a wider group of local organisations and landowners, taking inspiration from the success of the Great Crane Project in south-west England, which saw 93 cranes reintroduced to the Somerset Levels between 2010 and 2014. Indeed, invaluable consultancy support is being offered by the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust, the lead partner in the Great Crane Project, with the aim of replicating their impressive results – the establishment of a thriving colony of resident breeding birds – in the Cairngorms.

After years of careful planning, execution and subsequent monitoring, the Great Crane Project has provided a blueprint for crane reintroduction into the Cairngorms.

Crane reproduction is slow as although adult birds can live for up to 14 years, they don’t breed successfully until the age of four and most pairs raise just one chick a year. This limits their natural expansion and means that, without help, the few pairs that have begun to breed in the north-east of Scotland remain precarious, with the potential for wider recolonisation likely to take decades. Cranes are a species crying out for reintroduction to strengthen their numbers and ensure their comeback within Scotland is a permanent one.

The return of cranes as a breeding bird will help to catalyse the restoration of wet meadows, marshes and reedbeds. Crane habitat also favours a raft of declining wading birds, such as curlew, lapwing, redshank and snipe, as well as other declining species, including frogs, water voles and dragonflies. But Cairngorms Cranes is not just about nature – this is an initiative with people at its heart.

The Osprey Centre at Loch Garten attracts around 30,000 visitors each year, providing a valuable boost to the local economy and an equally valuable platform for education and engagement

It is almost 70 years since ospreys returned to the Cairngorms and in that time, researchers, volunteers, school children and a wide spectrum of local businesses have all felt the benefit of a landscape one prominent species richer. Cranes have just as much to offer. The project will involve a wide range of local people – as hands-on volunteers, advocates and bird monitors – to foster a real sense of connection to this special species and the habitat they rely on. This is about reshaping how we perceive and value nature, and shining a light on the role of its restoration in addressing climate breakdown and the challenges of retaining young people in rural communities.

"This is a fantastic opportunity to support local communities in tandem with ecological recovery."

Peter Cairns, SBP Executive Director

"This is a fantastic opportunity to support local communities in tandem with ecological recovery."

Peter Cairns, SBP Executive Director

Scotland stands at a crossroads in its relationship with nature. History paints a solemn picture. We’ve stripped our forests, drained our wetlands and eliminated many species that used to thrive here. Today, we have a choice: to accept our denuded natural heritage, or play a leading role in a global effort to restore abundance and diversity of life to our ecosystems. While some reintroduction targets present real challenges and provoke passionate debate, species such as the crane offer the promise of restoration with far less conflict. Fleeting visits by a few birds to the Cairngorms National Park in recent years have given us a tantalising glimpse into what could be achieved – now it’s time to turn that promise into an enduring wild spectacle, plucked from the past to last long into Scotland’s future.

With more than 8,000 hectares of suitable crane habitat already identified across the Park – including the epic expanse of the Insh Marshes – the scene is already set for their return. In the coming years, ongoing restoration of fen and peatland will enhance the Park’s ability to offer a home to cranes, and their reintroduction will in turn drive more habitat recovery. Work to transform the Insh Marshes into an exemplary natural floodplain is at the forefront of this. Natural processes will once again be given space to exert their influence as the River Spey is reconnected with its floodplain. Embankments will be removed, straightened burns re-meandered, and ditches blocked in areas susceptible to summer droughts.

In January 2022, Cairngorms Cranes begins a year-long development period during which local communities will be consulted, detailed planning will take place and permissions will be sought to lay the foundations for the return of this evocative bird. The Great Crane Project has shown it can be done – with resounding success – and given us an invaluable blueprint to adapt to our unique landscape, challenges and opportunities in the Highlands.

Cairngorms Cranes is riding on a new wave of rewilding-driven optimism. Bring back the crane and you not only reinstate a missing piece of our country’s ecological past, you open the door to a future rich in nature, where people and wildlife coexist as part of a big picture.