The Wolf: Too Wild For Scotland? (part 1)

As wolves continue to recolonise many parts of Europe, including heavily-populated countries like the Netherlands and Belgium, discussion around their return to the British Isles remains symptomatic of a nation undecided on its future relationship with nature.

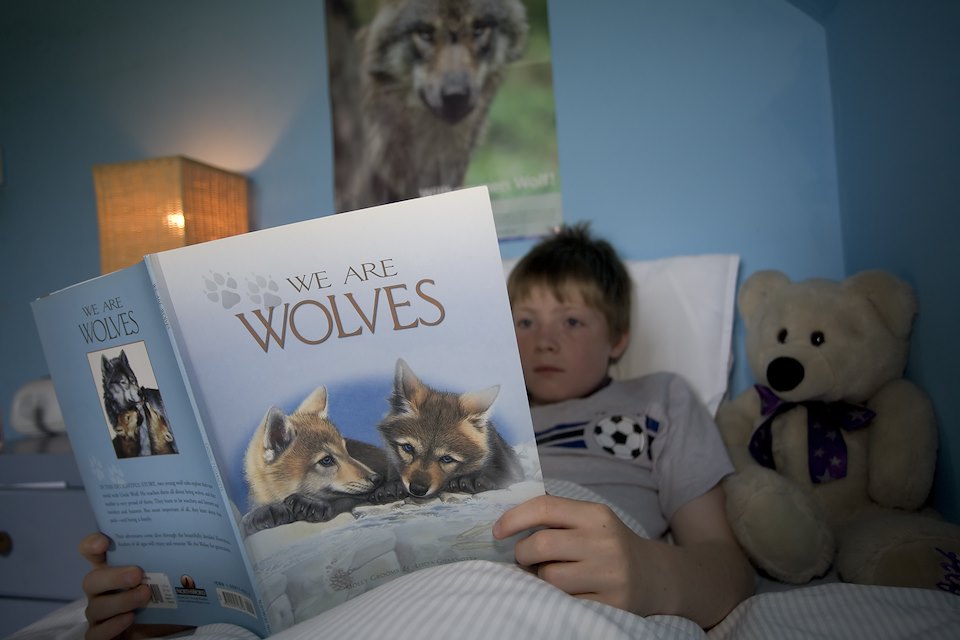

Predatory, fierce, and above all wild, wolves traverse our linguistic landscape, contributing to a lexicon freighted with fear: alarmists ‘cry wolf’; poor folk struggle to ‘keep the wolf from the door’; the unwary are cautioned against the ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’. And yet, the charismatic wolf attracts admiration as well as antipathy. As far back as Beowulf, we have named our kings and heroes after wolves, celebrating and even worshipping their perceived fearlessness, independence, and hunting prowess. Wolves have played so great a role in human culture and history that Margaret Attwood felt inspired to write, “all stories are about wolves.”

Wolves are embedded in our cultural consciousness.

In Europe, the wolf’s story has been one of resilience and recovery. In some places, prejudice and persecution are gradually giving way to respect and tolerance. Today Europe has twice as many wolves as the contiguous United States, despite being half the size and more than twice as densely populated. But in the absence of contact with the living animal, attitudes here in the UK remain petrified; we have become a nation of “fatally tidy-minded” gardeners whose collective wolf memories have grown blurred and ill-defined, while our capacity to live with wolves – or even to imagine doing so – has steadily eroded.

And yet, for a growing number of people, the wolf’s absence is keenly felt. With animals now reappearing across mainland Europe, re-occupying old haunts from Portugal to Norway, some conservationists have begun to wonder if we could restore the missing wolf to our own shores. Not long ago, such a proposal would have been considered eccentric at best, but the idea seems increasingly plausible. So, could we really reintroduce wolves to our crowded little island?

Though historical accounts vary, this ‘wolf stone’ in Brora, suggests that Scotland has had 300 years to get used to life without wolves.

Naysayers argue that wolves would be a menace in modern Britain. For them, reintroducing the ancestor of all domestic dogs seems akin to bringing back smallpox. “Why not reintroduce hyenas to Hampshire first?” they suggest, only half-jokingly. For many farmers and crofters, reintroducing wolves strikes at the core of an unwelcome rewilding agenda that has too often been carelessly imposed by perceived outsiders who remain both literally and figuratively remote from the consequences of their proposals. For rewilding sceptics, the wolf is not simply a potential threat to livestock and pets but is instead totemic of a wider more insidious threat to their whole world view.

For a growing number of people, the wolf's absence is keenly felt

For a growing number of people, the wolf's absence is keenly felt

Ranged against such opposition are those who value the wolf not just for itself, but for what it represents: as an indicator of ecosystem integrity; as an authentic symbol of wildness; or simply as a reminder of the fact that humans do not (and perhaps should not) stand unchallenged in their dominion over the natural world. The most zealous wolf supporters suggest that it has within its gift, a near-miraculous ecological healing power, a manifest destiny to restore balance to our degraded uplands and return vitality to our faltering natural systems.

Neither characterisation is entirely accurate, even if both borrow from the truth. Real wolves are more mundane and yet more marvellous than either the saint or the sinner of popular narrative. So, where might the flesh and blood wolf fit in to 21st century Scotland?

A PLACE FOR WOLVES?

It is often claimed that Scotland is just too small, too densely populated, or simply doesn’t have enough suitable habitat to support wolves. Others worry that reintroduced animals might thrive only too well and would inevitably spread from the remote, wilder areas where they naturally “belong”, to intrude upon and disrupt our more ordered, human-dominated world – becoming what Mary Douglas identified as “matter out of place”.

Unfavourable comparisons are thus drawn between “little” Scotland and the larger, seemingly wilder landscapes of Europe and North America, which currently support wolves. In reality, wolves are not uniformly present across any continental landmass. Instead, like every other large carnivore in the world today, they are restricted to discrete patches of remaining habitat – islands in a global landscape that is increasingly dominated by intensive agriculture, industrial development and urban sprawl.

And these remaining islands of wolf habitat are often no larger than the substantial tracts of suitable land in Scotland. Furthermore, it is the attitudes of the people that wolves share space with which is far more important than the nature of any particular habitat. Wolves themselves exhibit highly variable responses to human presence, sometimes avoiding human infrastructure such as roads, but at other times preferentially using them for ease of movement. They may select certain habitats that have been modified by humans such as forestry blocks, while at other times they can appear entirely indifferent to the human footprint.

Areas that are home to more people inevitably create more potential for conflict, but Scotland’s Highland region remains one of the most sparsely populated areas in Europe. Not all of its 26,484km2 is suitable for wolves, but these adaptable predators are able to thrive in environments ranging from dense forests to wide-open tundra, from mountain peaks to the tidal zone. Left alone in Scotland’s varied landscapes, wolves would thrive.

Of course, even within the Highlands, there will be areas where coexistence with wolves is more challenging, but there is certainly plenty of space. For comparison, the recently re-established wolf population now living along the Norwegian-Swedish border occupies a similar area to the Highland region, and these wolves coexist alongside nearly twice as many people. Similarly, the Apennine wolf population has persisted for decades in another comparably-sized area, while surrounded by ten times as many humans. Even the Iberian wolf’s core range in Northern Spain is only a little larger, but supports around 2000 wolves amidst many more people than live in the Highlands. In short, there can be no doubt that Scotland has enough space to support wolves.

Left alone in Scotland's varied landscapes, wolves would thrive.

HOW MANY WOLVES COULD SCOTLAND SUPPORT?

Wolf densities vary, being largely dependent on prey availability. Numbers range from as few as 0.3 wolves per 100km2 where prey is scarce, to as many as 7 or 8 wolves per 100 km2 in northern Spain or the Abruzzo region of Italy. However, the average is probably closer to 2, suggesting that the Highland region could (in theory) support as many as 500 individuals.

Wolves are primarily predators of large hoofed mammals and in Scotland, the majority of their diet would likely be made up of our two dominant deer species, the red deer and the roe. Exact numbers are the subject of debate, but Scotland is believed to be home to around 400,000 red deer and 200-350,000 roe deer. Not all these deer live in the Highlands of course, but the region likely supports several hundred thousand deer.

A single wolf needs 3-4 kg of meat per day, equivalent to about 20 red deer a year. Even if the Scottish Highlands one day became home to 500 wolves, they would still only be consuming around 10,000 red deer a year – less than that if they were eating roe deer and other prey species as well. For comparison, 80,000 red deer and 45,000 roe deer were culled by stalkers in Scotland in 2017/2018. Clearly, there is enough wolf food on our hills.

In Finland, wild wolves not only perform the vital ecological role of apex predators, but have become valuable tourism assets attracting enthusiasts from all over Europe.

However, if a wolf reintroduction attempt went well, and a small founder population was carefully supplemented over time, the carrying capacity of the Highlands might eventually be reached. What might happen then? Would the wolf population be large enough to be self-sustaining without suffering inbreeding (a threshold biologists call a minimum viable population)? And would wolves continue to spread southwards into increasingly human-dominated landscapes?

Modelling suggests that a population of 200-250 wolves should be large enough to avoid inbreeding and ensure the best chance of long-term viability. Furthermore, in practice, many large carnivore populations in Europe have persisted for decades at lower numbers than this. If only half the Highland region came to be occupied by wolves, the population would still likely be large enough to be self-sustaining without any loss of genetic diversity.

Theoretically, Scotland has both the space and the food with which to support a viable wolf population; but just because Scotland could reintroduce wolves, it doesn’t necessarily follow that we should. We need to be sure that communities are ready to coexist with wolves. Wolf enthusiasts have too often been guilty of overlooking or downplaying the realities of living with wolves or – just as important – the perceived threats that wolves pose to a rural population that has not lived with large carnivores for hundreds of years. It is clear that wolves could live alongside us; it remains much less clear whether we are prepared to live with them, or whether indeed the wolf remains too wild for Scotland.